Tinfoil Chat

Tinfoil Chat (TFC) is a FOSS+FHD peer-to-peer messaging system that relies on high assurance hardware architecture to protect users from passive collection, MITM attacks and most importantly, remote key exfiltration. TFC is designed for people with one of the most complex threat models: organized crime groups and nation state hackers who bypass end-to-end encryption of traditional secure messaging apps by hacking the endpoint.

State-of-the-art cryptography

TFC uses XChaCha20-Poly1305 end-to-end encryption with deniable authentication to protect all messages and files sent to individual recipients and groups. The symmetric keys are either pre-shared, or exchanged using X448, the base-10 fingerprints of which are verified via an out-of-band channel. TFC provides per-message forward secrecy with BLAKE2b based hash ratchet. All persistent user data is encrypted locally using XChaCha20-Poly1305, the key of which is derived from password and salt using Argon2id, the parameters of which are automatically tuned according to best practices. Key generation of TFC relies on Linux kernel's getrandom(), a syscall for its ChaCha20 based CSPRNG.

Anonymous by design

TFC routes all communication exclusively through the Tor anonymity network. It uses the next generation (v3) Tor Onion Services to enable P2P communication that never exits the Tor network. This makes it hard for the users to accidentally deanonymize themselves. It also means that unlike (de)centralized messengers, there's no third party server with access to user metadata such as who is talking to whom, when, and how much. The network architecture means TFC runs exclusively on the user's devices. There are no ads or tracking, and it collects no data whatsoever about the user. All data is always encrypted with keys the user controls, and the databases never leave the user's device.

Using Onion Services also means no account registration is needed. During the first launch

TFC generates a random TFC account (an Onion Service address) for the user, e.g.

4sci35xrhp2d45gbm3qpta7ogfedonuw2mucmc36jxemucd7fmgzj3ad. By knowing this TFC account,

anyone can send the user a contact request and talk to them without ever learning their

real life identity, IP-address, or geolocation. Protected geolocation makes physical

attacks very difficult because the attacker doesn't know where the device is located on

the planet. At the same time it makes the communication censorship resistant: Blocking TFC

requires blocking Tor categorically, nation-wide.

TFC also features a traffic masking mode that hides the type, quantity, and schedule of communication, even if the network facing device of the user is hacked. To provide even further metadata protection from hackers, the Internet-facing part of TFC can be run on Tails, a privacy and anonymity focused operating system that contains no personal files of the user (which makes it hard to deduce to whom the endpoint belongs to), and that provides additional layers of protection for their anonymity.

First messaging system with endpoint security

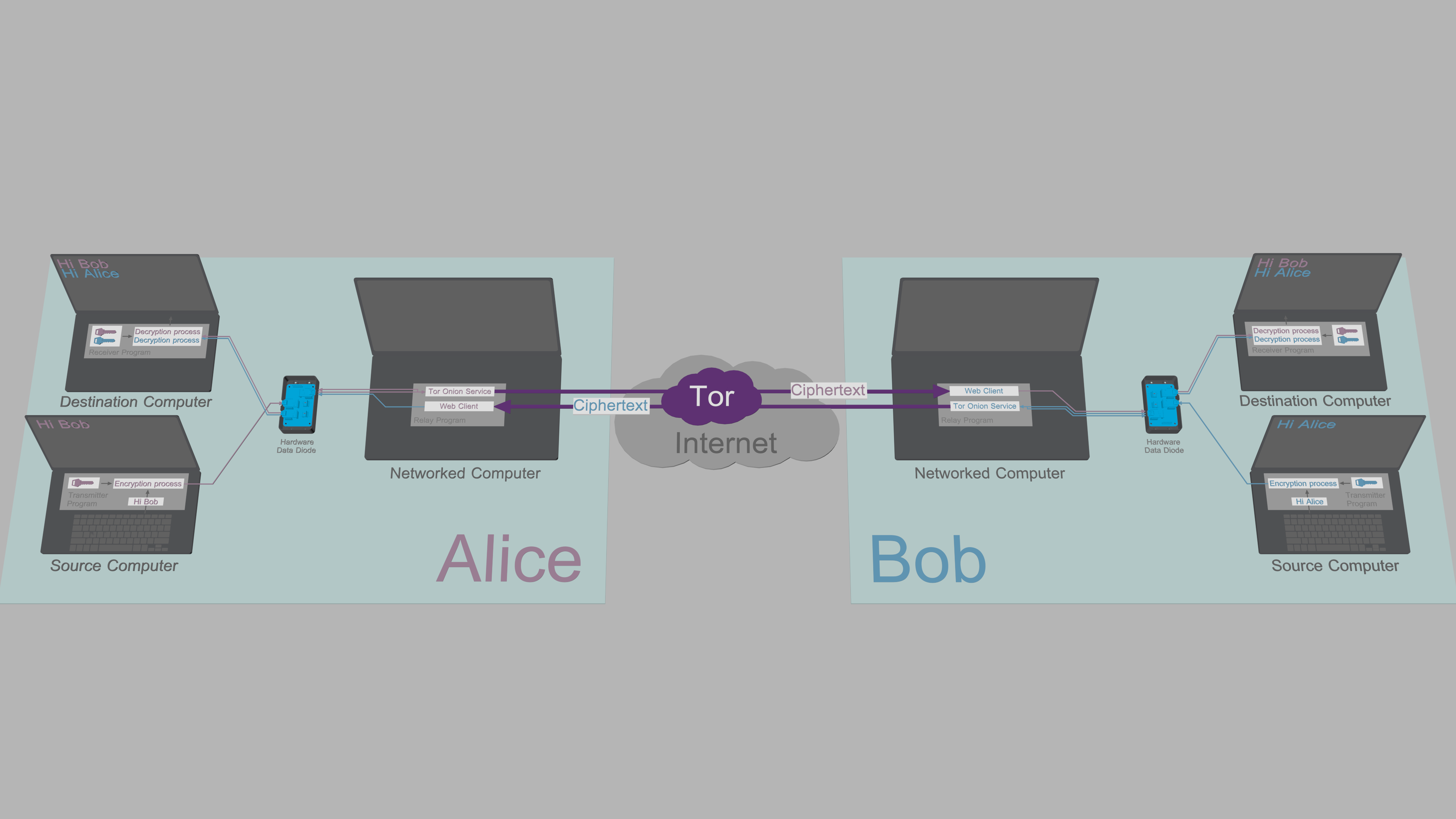

TFC is designed to be used in hardware configuration that provides strong endpoint security. This configuration uses three computers per endpoint: Encryption and decryption processes are separated from each other onto two isolated computers, the Source Computer, and the Destination Computer. These two devices are dedicated for TFC. This split TCB interacts with the network via the user's daily computer, called the Networked Computer.

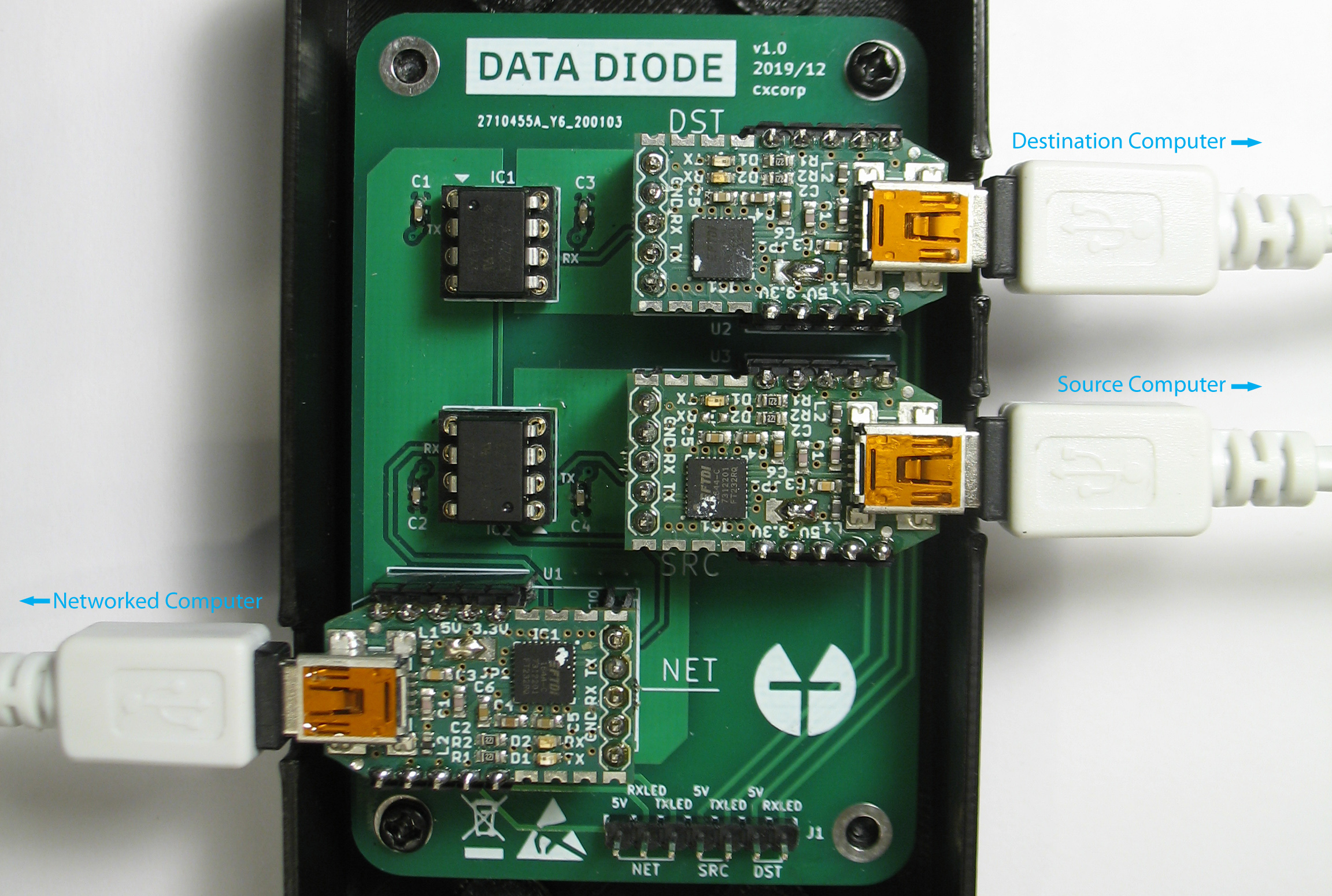

In TFC data moves from the Source Computer to the Networked Computer, and from the Networked Computer to the Destination Computer, unidirectionally. The unidirectionality of data flow is enforced, as the data is passed from one device to another only through a free hardware design data diode, that is connected to the three computers using one USB-cable per device. The Source and Destination Computers are not connected to the Internet, or to any device other than the data diode.

Optical repeater inside the optocouplers of the data diode enforce direction of data transmission with the fundamental laws of physics. This protection is so strong, the certified implementations of data diodes are typically found in critical infrastructure protection and government networks where the classification level of data varies between systems. A data diode might e.g. allow access to a nuclear power plant's safety system readings, while at the same time preventing attackers from exploiting these critical systems. An alternative use case is to allow importing data from less secure systems to ones that contain classified documents that must be protected from exfiltration.

In TFC the hardware data diode ensures that neither of the TCB-halves can be accessed bidirectionally. Since the protection relies on physical limitations of the hardware's capabilities, no piece of malware, not even a zero-day exploit can bypass the security provided by the data diode.

How it works

With the hardware in place, all that's left for the users to do is launch the device specific TFC program on each computer.

In the illustration above, Alice enters messages and commands to Transmitter Program running on her Source Computer. The Transmitter Program encrypts and signs plaintext data and relays the ciphertexts from Source Computer to her Networked Computer through the data diode.

Relay Program on Alice's Networked Computer relays commands and copies of outgoing messages to her Destination Computer via the data diode. Receiver Program on Alice's Destination Computer authenticates, decrypts and processes the received message/command.

Alice's Relay Program shares messages and files to Bob over a Tor Onion Service. The web client of Bob's Relay Program fetches the ciphertext from Alice's Onion Service and forwards it to his Destination Computer through his data diode. Bob's Receiver Program then authenticates, decrypts and processes the received message/file.

When Bob responds, he will type his message to the Transmitter Program on his Source Computer, and after a mirrored process, Alice reads the message from the Receiver Program on her Destination Computer. All this happens seamlessly and automatically.

Why keys and plaintexts cannot be exfiltrated

The architecture described above simultaneously utilizes both the classical and the alternative data diode models to enable bidirectional communication between two users, while at the same time providing hardware enforced endpoint security:

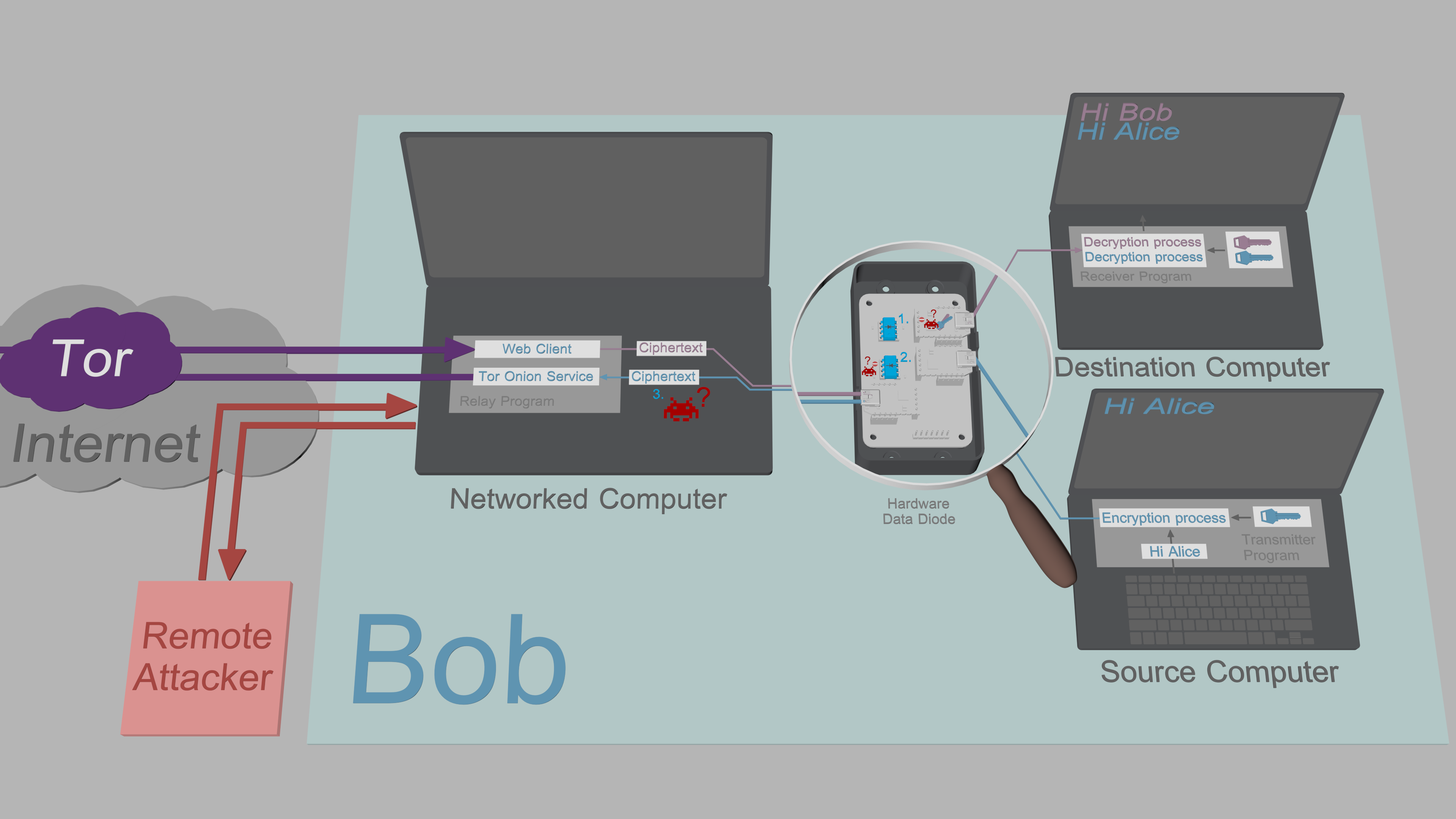

-

The Destination Computer uses the classical data diode model. This means it can receive data from the insecure Networked Computer, but is unable to send data back to the Networked Computer. The Receiver Program is designed to function under these constraints. However, even though the program authenticates and validates all incoming data, it is not ruled out malware couldn't still infiltrate the Destination Computer. In the event that would happen, the malware would be unable to exfiltrate sensitive keys or plaintexts back to the Networked Computer, as the data diode prevents all outbound traffic.

-

The Source Computer uses the alternative data diode model. This means it can output encrypted data to the insecure Networked Computer without having to worry about being compromised. The data diode lacks the hardware that would allow transmission of data to the Source Computer, which protects the Source Computer from all remote attacks. The Transmitter Program is also designed to work under the data flow constraints introduced by the data diode; To allow key exchanges, the short elliptic-curve public keys are input manually by the user.

-

The Networked Computer is designed under the assumption it can be compromised by a remote attacker: All sensitive data that passes through the Relay Program is protected by authenticated encryption with no exceptions. Since the attacker is unable to exfiltrate decryption keys from the Source or Destination Computer, the ciphertexts obtained from Networked Computer are of no value to the attacker.

Qubes-isolated intermediate solution

For some users the APTs of the modern world are not part of the threat model, and for others, the requirement of having to build the data diode by themselves is a deal-breaker. Yet, for all of them, storing private keys on a networked device is still a security risk.

To meet these users' needs, TFC can also be run in three dedicated Qubes virtual machines. With the Qubes configuration, the isolation is provided by the Xen hypervisor, and the unidirectionality of data flow between the VMs is enforced with Qubes' qrexec framework. This intermediate isolation mechanism runs on a single computer which means no hardware data diode is needed.

Supported Operating Systems

Source/Destination Computer

- Debian 11

- PureOS 10.0

- *buntu 22.04 LTS

- Pop!_OS 22.04 LTS

- Linux Mint 21.1

- LMDE 5

- Zorin OS 16.2

- Qubes 4.1.2 (Debian 11 VM)

Networked Computer

- Tails 5.12

- Debian 11

- PureOS 10.0

- *buntu 22.04 LTS

- Pop!_OS 22.04 LTS

- Linux Mint 21.1

- LMDE 5

- Zorin OS 16.2

- Qubes 4.1.2 (Debian 11 VM)

More information

Threat model

FAQ

Security design

Hardware Data Diode

Breadboard version (Easy)

Perfboard version (Intermediate)

PCB version (Advanced)

How to use

Installation

Master password setup

Local key setup

Onion Service setup

X448 key exchange

Pre-shared keys

Commands